Though his discoveries were on a microscopic scale, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s impact was anything but small. Widely seen as the father of microbiology, Leeuwenhoek’s single-lensed microscopes allowed him to be one of the first to document microbial life. In celebration of his birthday, let’s zoom in on his life, career, and legacy.

Becoming a Recognized Figure on a Global Scale

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was born on October 24, 1632, in the city of Delft in the Dutch Republic (modern-day Netherlands). He had little formal education and became a bookkeeper’s apprentice in a linen-draper’s shop in Amsterdam at the age of 16.

A portrait of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723). This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1928, via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1654, Leeuwenhoek returned to Delft and opened up his own draper’s shop. While in Delft, his social status gradually grew and he received several lucrative positions. In 1660, he became the chamberlain for the sheriffs in the city hall. Nine years later he became the official wine gauger of Delft, where he was in charge of local wine imports.

In addition to helping Leeuwenhoek establish himself locally, his draper work also helped him become a recognized figure on a global scale….

Details, Details, Details: Developing the Microscope

Leeuwenhoek’s work as a draper required him to have a deep understanding of the quality of cloth so that he could better market and price his goods. To examine cloth in greater detail he turned to microscopes. However, he found that even the compound microscopes of the day were only capable of magnifying objects by 30 times. To overcome this roadblock, he decided to try his hand at grinding lenses and developing microscopes himself. In this work, he found great success, as he was able to produce powerful microscopes — one of of which was able to magnify objects by 275 times their normal size! This level of magnification wouldn’t be challenged in his lifetime, giving Leeuwenhoek a monopoly on the microscopic world for decades. (This is not to say that the past work of other innovators didn’t help drive Leeuwenhoek’s success. Beyond his desire for seeing threads in more detail, Leeuwenhoek may have been partially inspired by Robert Hooke’s popular, illustrated book on microscopy, Micrographia.)

Replica of a microscope made by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, taken by Jeroen Rouwkema. This photo is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

While examining threads with his newly developed microscope, Leeuwenhoek noticed tiny organisms and recorded his findings. This inspired him to examine other materials, including a sample of pond water filled with green algae. Untrained as a scientist but with a craving for knowledge, Leeuwenhoek tracked these discoveries thoroughly, writing down and sketching what he had seen. Originally apprehensive to share this information, Leeuwenhoek was urged by friend and Dutch physician Reiner de Graaf to write to the Royal Society in London about his work. This began a correspondence between Leeuwenhoek and the society that would continue through the former’s entire life.

Leeuwenhoek preferred to work alone, was not formally trained, and never published a traditional scientific paper in Latin. Partially because of this, he faced resistance from the Royal Society about his writings. After a group of observers (including Sir Robert Gordon) viewed and confirmed his findings, Leeuwenhoek’s observations were completely accepted by the Royal Society. This helped shape the world’s understanding of the existence of microscopic organisms. He would even be elected to this prestigious institution in 1680.

The Father of Microbiology

Having the technology to see a world that had only vaguely been understood before, Leeuwenhoek was one of the first to write on some of the most recognizable microorganisms known today. Through his microscopic study, he was the first to see infusoria (various freshwater microorganisms) and bacteria (viewed from scraping from his teeth). His letters to the Royal Society also contained detailed analyses of fleas and weevils (small beetles known for their elongated snouts), which helped to discredit the idea that both of these creatures were spontaneously generated.

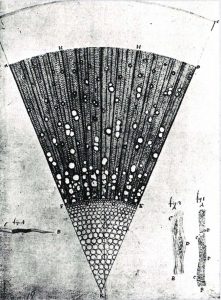

A drawing by Leeuwenhoek of a microscopic section of a one-year-old ash tree. This photo is in the public domain where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or fewer. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Leeuwenhoek wrote hundreds of letters on his scientific findings to the Royal Society and other institutions. His studies and letters earned him visits from world leaders of the time, including William III of Orange, Mary II of England, and Peter the Great. By the time of his passing, Leeuwenhoek had become the most well-known figure in the field of microscopic study, having created more than 500 optical lenses and at least 25 single-lens microscopes.

Today, Leeuwenhoek is widely regarded as the father of microbiology and the preeminent figure in the field of microscopy.

Further Reading

- Learn more about the history of the microscope here:

- Robert Hooke, an English scientist best known for his book Micrographia and coining the term “cell”

Comments (0)